Istanbul Convention: Numbers and the Other End of the Thread

It is as if, across the world, the male mind is thinking, "Let's appear as if combating violence; so that the inequalities existent at the other end of this thread remain invisible." Every reason presented for withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention is tantamount to declaring that gender equality is unachievable and inappropriate and shall not be allowed.

We are being killed… Yet somehow, this is not considered to be a major problem. We are being killed, and worse still, those of us who are alive end up worse than dead. We are staring at death. Our life spaces are dying as well. Or we kill our own selves. Few of us understand this fact. Few of us can explain what they understand.

In the occasional training programs that I deliver, I ask: “Could you estimate the number of femicides reported and quantified by the media and similar platforms, in the last year?” The participants’ estimates increase year after year. The estimates are way higher than the actual figures, and when I disclose the latter, the participants react by saying, “Oh, really! Is that the actual figure? I thought it would be much higher.”

We are either killed, or somehow survive, only to suffer from various forms of violence. We may or may not survive while experiencing the life imposed upon us by the prevalent gender regime. We are not simple icons in statistical charts. We are not the “rising numbers” in studies or media scans on violence.

But our death or survival whets the public’s appetite and draws its attention only when the numbers grow ever higher; only then do we become a topic worthy of discussion. Our death or survival leaves a few short phrases in social media feeds replete with images of cheerful breakfasts among friends, funny cat photos, cacti in bloom, a few slogans, and various business news.

Otherwise, our death and life constitute an expense item in the public sector’s “cost” calculations…

I remember that at an international meeting, in a presentation before public sector officials, the following phrase was used: “Violence against women swells the costs in the public budget by billions of dollars.” Upon hearing these billion dollar figures deemed to be “remarkable”, we are expected to exclaim, “Oh my God, that’s way too much!”

Let us add the following to the cost of violence towards women: Women suffering from violence cannot work or produce, not to mention their hospital and treatment expenses. When divorce comes into play, the cost increases further.

Let us imagine how much further the costs would increase if the state were to fulfill its public responsibilities? The state would have to protect women and prevent violence; then there are costs associated with rehabilitation, investigation and criminal enforcement. The state would also have to cover the costs of imprisoned men. This would certainly provide a boost to the economy, but it would cost a lot nonetheless. So, let us avoid all of these cost items.

Could we continue business as usual if we were to slash costs somewhat? If the cost dropped to one dollar, it would be manageable, right? Couldn’t we stop combating violence then? How many femicides can our budget cover this year? Does fatality decrease or increase the cost, in your view?

Solidarity Saves Lives!

Which calculation could change our opinion on violence? When one objects to this grave ethical error, they respond, “Well, that’s the only perspective that institutional structures would understand.” Nothing could be farther from the truth! Public institutions and their workforce are ultimately composed of individuals who experience gender-based violence first hand.

And like everyone else, they need to hear this:

Not one woman less!

Your eyelash shall not fall to the ground!

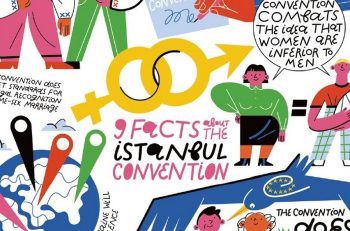

To those who ask, “How can one achieve that? What would be the right method?”, women across the world give a clear answer: the Istanbul Convention. The Istanbul Convention rendered visible what we had been saying for over 20 years.

Long before the Istanbul Convention came into force in 2011, women across the world had built pressure on the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) with their reports, gradually getting results.

There are two dynamics underlying this convention upholding women’s demands and placing these within the framework of fundamental human rights. The first is the shared experience of subjugation that women face under the patriarchal social order, and the second is their experience of solidarity showing them that they can struggle against domination only collectively.

Over the years, we waged so many struggles, learning where to highlight our differences and where and how to build our unity. We have thus turned difference and unity, merger and separation into our strength, rather than weakness. We know better than anyone else how we separate and then reunite. As such, we best know how to achieve this once again, and not anybody else.

One of the nine fundamental human rights conventions of the United Nations (UN), CEDAW had at first not covered the subject of violence in its main text. It is only thanks to women’s efforts that this shortcoming in such a major convention was remedied, first by the general recommendation no. 12 in 1989 and then by the general recommendation no. 19 in 1992. The unquenchable demand for combating gender-based violence towards women was finally met by the Istanbul Convention.

This is not an ordinary historical account. This story actually points out something else. “The Istanbul Convention saves lives”; yes, but do you know what else does so? Solidarity. This is what this story is telling us. It shows that we have been the protagonists of this struggle since its inception. The Istanbul Convention is a perfect example of what women’s solidarity can achieve.

And do you know why we won’t give up? Because we know that there would be no reason why a state truly intent on taking sincere, effective and realistic measures against violence to withdraw from this convention. Whether conservative, liberal, progressive or conservative, any state across the world has to assume its responsibility in combating violence. The Istanbul Convention explains to public authorities in an elaborate manner how to fulfill this responsibility, and how to combat violence.

The combat against gender-based violence towards women existed long before states began viewing it as their public responsibility, and their need to assume this responsibility was discussed at the 1993 Vienna conference. Women’s solidarity paved the way for revising the sexist language in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and drafting the convention for the prevention of all kinds of discrimination against women as well as the Istanbul Convention. Then, this same solidarity defended its gains. And it will always do so.

Istanbul convention was not the first; it will not be the last

I hark back to the days when I worked in a women’s shelter. I had suggested that we paint a tree on the wall: a huge tree with branches offering a solution to each and every problem. With branches that read income, education, financial support, health, security, housing and empowerment. Then the branches would divide further into twigs representing a multitude of public services, civil society support schemes and various other solutions. At the ends of the branches, there would be flowers or fruits bearing names like empowerment, liberty, confidence, bliss, health, unity and love. So that upon stepping into the shelter, women would first see that beautiful tree. Then, they would again lay eyes on that tree whenever they walked through that corridor. They would stand before it and ponder, marking various branches for themselves. I wanted that tree to provide us all with oxygen, relief and power.

The Istanbul Convention represents that tree in my eyes. Yet now, I feel as if someone has burned or chopped that tree down. It is as if all my solution proposals have disappeared along with that tree. Whenever I tell women that the convention saves lives, I also worry whether they will fear for their lives, now that Turkey has withdrawn from the convention.

I fear casting a shadow over the powerful women’s movement and solidarity, seeming to suggest that women are alone and unprotected now that the convention is no more.

Every time I use the phrase “Istanbul Convention saves lives”, I stop and think for a moment. I suddenly become the first woman to lay eyes on that tree. Then I think to myself: Don’t worry, “Istanbul Convention saves lives”, yet it is actually women’s solidarity that keeps the Istanbul Convention alive. Don’t worry, because you shall never walk alone! Because, we won’t give up!”

Can we combat violence without the Istanbul convention?

Can Turkey, the first country to express out loud its wish to withdraw from the convention, continue to combat violence? Can one combat violence only when such a convention exists? Don’t the ministries and relevant institutions give the message that the fight against violence will continue at full speed?

The real question here is whether these messages are realistic and sincere. We have all gone through a long process across the world and in Turkey, prompting us to give a negative answer to this question.

Gender-based violence is among the most conspicuous instruments of a binary society based on the domination of one sex over the other. As in Hartmann’s famous definition, violence is the most conspicuous manifestation of patriarchy, a system of control over women’s labor and body. Yet no one yields to violence and murder.

If one end of the thread is combating violence, let us not forget that the other end leads to inegalitarian power relations between genders and then a social structure based on these power relations. We also see education, healthcare, marriage, inheritance rights, participation in politics and all levels of decision-making, participation in economic life, decent work conditions, equal pay, division of domestic chores, and sharing of income. In all these dimensions, we see that the current social order perpetuating men’s privileged lives has to be transformed.

So, it is as if, across the world, the male mind is thinking, “Let’s appear to combat violence so that the inequalities found at the other end of this thread remain invisible.” It also seems to think, “Let us combat violence in such a way that we can maintain gender-based inequality.” This is what I understand when I hear the phrase, “combating violence in accordance with our traditions and values”. For this reason, I don’t think that those rejecting the Istanbul Convention can give a realistic and sincere message of combating violence. Each pretext presented for withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention is tantamount to declaring that gender equality is unachievable and inappropriate and shall not be allowed.

People in this country lost so much time whenever the state stated the obvious. They took so much time to realize their mistake. How much effort they spent to explain to themselves and others their regret for supporting the government years ago although they were indeed quite right back then.

I have drawn the following conclusion from ongoing political debates: The opposition should not limit itself to a passive attitude of only targeting those holding power and reacting to the latter’s actions and influence.

On the contrary, the opposition must engage in a praxis incorporating every neglected issue and giving voice to everyone, to reach the goal of social progress.

It is precisely because of this that there is only one way that I know, recognize, and uphold. We Need Feminism. ‘Why?’ you may ask. Because, my conception of feminism is built upon collective empowerment, learning from one another, and solidarity…

Bizi Takip Edin