Publishing in Kurdish Language: Pushing Forward

It is safe to say that today, Kurdish language publishing has turned into an industry that meets Kurds' needs to a large extent. However, one might also add that its progress has been frequently interrupted by outside forces, slowing down to a pace of “two steps forward, one step back.”

The Peace Process between the Turkish government and the Kurdish militia organisation that went on through 2013 to 2015 had expanded the public space for Kurdish Language. It had an important impact on the learning and use of the language. With increased interest towards Kurdish and Kurds, Kurdish language publishing sector had gone through a relatively favourable period. However, after it broke down and the armed conflict resumed – this time in urban areas as well – great challenges began to emerge. Kurdish publishers once again faced a situation reminiscent of the 1990s, a dark period in Turkey’s history with all out military operations. Directly affected by the itinerary of the Kurdish matter in Turkey, language and culture publications have been going through a rough patch and facing rights violations since 2016.

Issued by the Kurdish Studies Centre, the ‘Rights Violations in Kurdish Language Cultural Publishing’ report focuses on the problems and rights violations experienced by Kurdish publishers.

Based on monitoring work, the report divides the rights violations in question into the following categories:

Discrimination and rights violations in the fields of printing and distribution constitute a major problem for Kurdish publishers. Distribution companies, bookstore chains and online bookstores tend to not give a prominent place to Kurdish language books. Many volumes shipped via the state-owned PTT are returned to sender, which is another problem ongoing since the 90s.

The government’s executive decrees and replacement of elected mayors by state-appointed trustees also have a negative effect on Kurdish publishing. Kurdish publishers have difficulty attending book fairs organized by municipalities headed by these trustees, Kurdish language books are removed from municipal libraries and Kurdish language kindergartens are closed -all of which reduce the visibility of the language. Furthermore, many public employees, who constituted an important part of the readership, were dismissed by the government’s executive decrees.

Kurdish publishers are also prevented from attending book fairs and face related rights violations, which further weakens their situation. Already economically fragile, Kurdish publishing houses are not invited to book fairs, their applications to participate are rejected or cancelled at the last minute, or their booths are relocated, all of which further aggravate their disadvantaged position.

The Ministry of Culture’s grants are distributed in a discriminatory manner; for instance, Kurdish writers are not eligible for “first book” grants since only Turkish language publications are supported. Libraries affiliated with the Ministry rarely purchase books from Kurdish publishers, further aggravating their problems. For example, the Ministry bought a total of 4 volumes from Avesta so far; however, only one of them was in Kurdish.

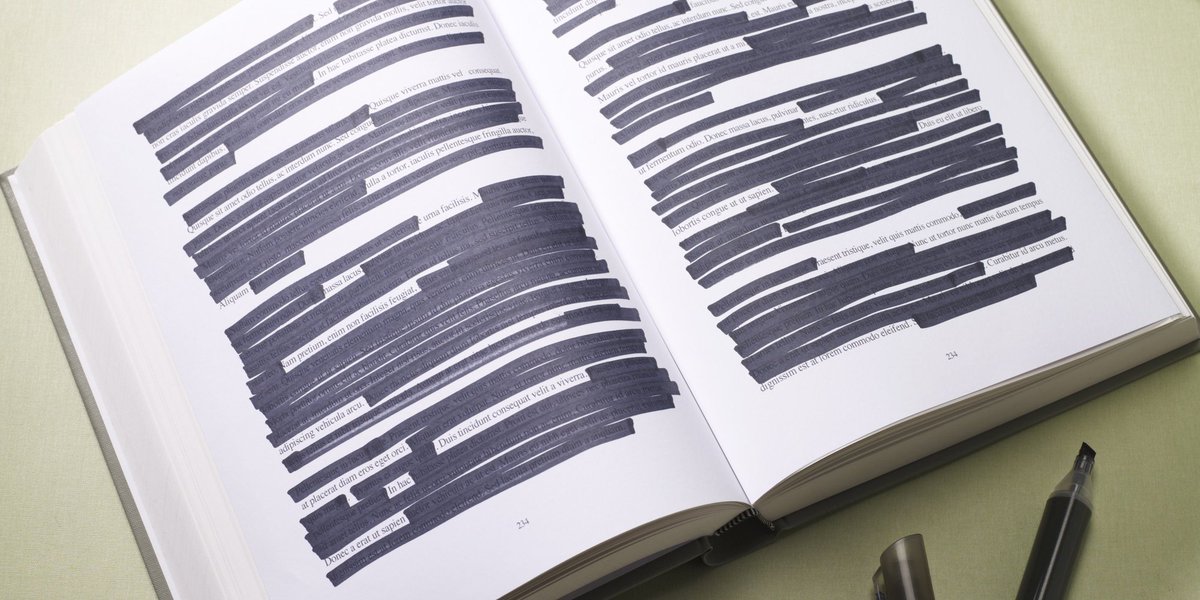

The banning and confiscation of books is another thorny issue for Kurdish publishers. According to the information provided by publishers, since 2009, at least 117 books published by Kurdish publishing houses were banned. It is indicated that 102 volumes published by Aram and 15 by Avesta (two well-known Kurdish publishing companies) were banned after the failure of the Peace Process.

Kurdish language books sent to prisons are not given to the prisoners, in another violation of rights for both publishers and inmates. Publishers interviewed for the report state that almost always their books are banned or confiscated because they drew the attention of police officials organizing a house raid because of their title, cover, etc. or because prison administrations decide that they are objectionable.

Publishers also indicate that certain quite large volumes were banned within 24 hours after notification to the Police Department, and that it is not possible to read and evaluate these volumes in such a short space of time. They argue that, “These books were banned so rapidly; simply because they were published by Kurdish publishers and contained words such as Kurdistan (a word deemed to be offensive by Turkey’s state or executive organs).”

The legal pressure on publishers is another area of rights violations with a negative effect on Kurdish publishing. On top of the above-mentioned issues, there is direct discrimination, repression and rights violations targeting Kurdish authors and publishing house executives. More and more publishers were detained after the failure of the Peace Process and the return to armed conflict. Abdullah Keskin, the concessionaire of Avesta Publishing and Azad Zal, an executive with J&J Publishers, both faced legal proceedings in such an atmosphere.

‘Propaganda’ Charges as a Cover for Arbitrary Action

Politicians, the civil society, and Kurdish readers must all play a role to enable the independent progress of Kurdish publishing.

“Propagandising for a terrorist organization” is the main charge levelled against Kurdish publishers during investigations and prosecutions, or to ban their books. This charge has now turned into an instrument that criminalizes and limits the freedom of expression of a large number of civil society, political and media organizations in Turkey.

However, rights violations go much further. For example, even books published before the above-mentioned Kurdish militia organisation, PKK (that is Kurdistan Worker’s Party), was established are accused of “propagandising for a terrorist organization” referring to the PKK; which proves the arbitrary use of such accusations.

The report also includes suggestions to Kurdish publishers’ problems. It argues that the most important step to solve the problem would be to recognize Kurdish as an official language of the country, so as to establish social and legal equality.

Other solution proposals include the revival of elective Kurdish courses in schools, the reinvigoration of Kurdology Institutes, ending discriminatory practices especially in state-owned institutions, purchase of Kurdish language books by Ministry of Culture and affiliated organizations to place these volumes in libraries, ending the controversial “terror propaganda” charges to offer freedom of expression to Kurdish publishers, and support for multilingual education.

To conclude, one might say that Kurdish publishers have created an industry which meets the needs of Kurds to a large extent -not only responding to existing demand, but also creating new demand for Kurdish books. However, one might also add that this journey has been interrupted frequently by outside factors, slowing down to a pace of “two steps forward, one step back”. Politicians, the civil society, and Kurdish readers must all play a role to enable the independent progress of Kurdish publishing.

Bizi Takip Edin